In Africa, the mythical Sankofa bird looks back while moving forward, a symbol that conveys the power of remembering the past while preparing for the future. At Cleveland Public Library, this visual metaphor also serves as a design inspiration for the new Hough Branch, which is slated to open the summer of 2022.

Hough Branch will be transformed as part of the Library’s Facilities Master Plan, a major capital project that will reimagine the entire Cleveland Public Library system by rebuilding or significantly renovating every branch library over the next decade. This project ensures the city’s libraries are safe, modern, accessible, and inclusive spaces that will benefit the Cleveland community for many years to come.

In Hough’s case, this process entails designing and constructing a new building in a new location. It’s all part of a larger vision for the Cleveland Public Library system—one that, like that Sankofa bird, honors the past while forging ahead into the future.

Past, Present, Future

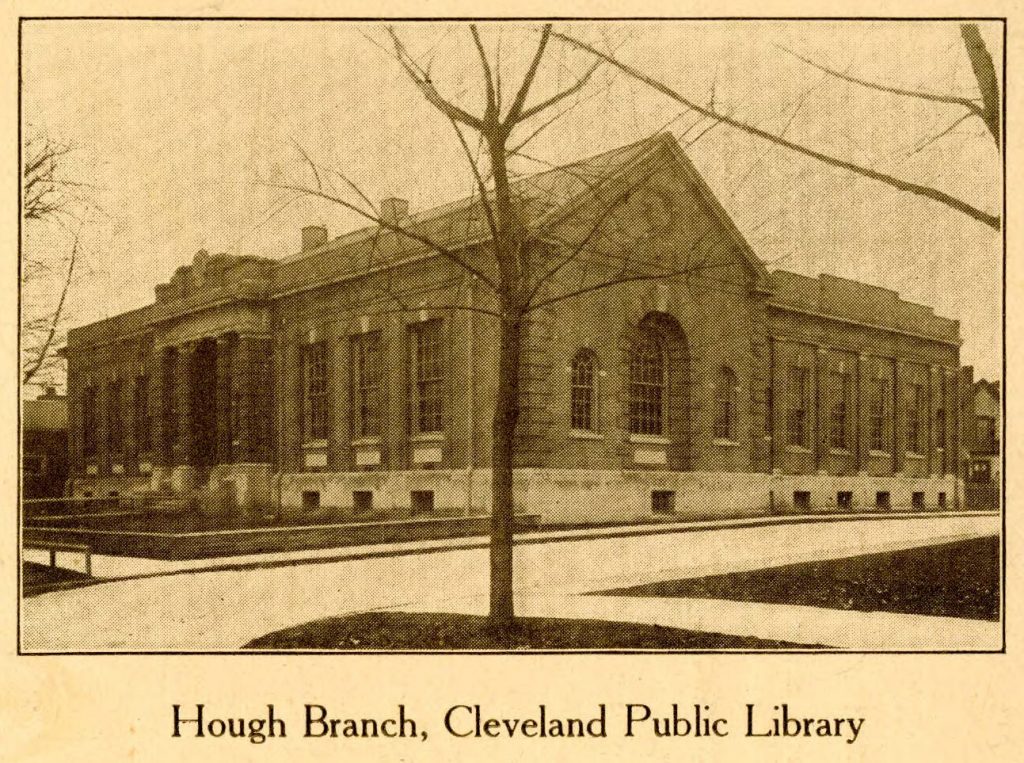

The presence of a library in Hough extends back to 1907, when Cleveland Public Library opened a branch in the neighborhood. That building was eventually renovated, renamed, and ultimately reborn as an African American museum. The current Hough Branch opened in 1984 at 1566 Crawford Road and has served the community since. In the coming years, Hough will move to a newly constructed building offering more space, modern amenities, moveable workstations, meeting rooms, an improved children’s area, and a more attractive, welcoming outdoor space.

“We’re especially excited about a new children’s area,” says Hough Branch Manager Lexy Kmiecik. “Having inviting areas in the library for both adults and children is so important.”

Hough Branch is home to the Hough Reads program, family literacy events, and many programs of value to residents. While the COVID-19 pandemic has put in-person programs on hold, plans for the new building are moving ahead as scheduled. In fact, the pandemic has only highlighted the importance of designing flexible library interiors that allow for various configurations based on patron and programming needs.

The new branch will have plenty of windows to bring in natural light and will make an engaging visual impression in the neighborhood. The Sankofa metaphor, meanwhile, will make a subtle appearance in the building’s exterior design, which will “fold in” on itself just as the Sankofa bird turns to look back. The branch also takes some inspiration from League Park, the historic ballpark that opened in 1891 and was home to teams from Major League Baseball, the National League, and the Negro American League. The new library will be located near the League Park site at Lexington Avenue and E. 66th Street.

While Kmiecik acknowledges that changing locations may present a challenge for some patrons, gaining a new and improved building positioned on a bus line is a clear benefit. Besides, an important constant will endure the move: the library employees.

“Hough has the best staff,” Kmiecik says. “They’re a seasoned staff who really know their patrons and the history of the area—and we’re all excited to continue to serve our community in our new location.”

Design and Innovation

Throughout every stage of its Facilities Master Plan, Cleveland Public Library has worked to promote diversity and inclusion, including in the architecture firm selection process. The new Hough Branch is designed by Moody Nolan, the largest African American-owned design firm in the country. Moody Nolan architects have experience designing library buildings as well as a larger appreciation for the value of public libraries.

“In Ohio, the conversations about community challenges often surround kindergarten readiness, reading, and access to childcare,” says Moody Nolan CEO Jonathan Moody, AIA, NOMA. “Cleveland Public Library is responding to those deeper issues in the city. Not every facility or building has to do that, but libraries do.”

Project Architect Jakiel Sanders, AIA, NOMA, adds that library architecture has evolved from the days of Carnegie libraries in the early 20th century. Those buildings, he says, were classical, symmetrical, and created the staid impression of a “temple of learning.” But contemporary libraries serve many different purposes.

“We want to convey that today’s libraries are so much more than a quiet place to read,” Sanders explains. “They’re places for community gatherings, where people get news and education, and where children get homework help and receive meals. Libraries are community hubs, and we want to symbolize that with Hough’s architecture.”

When the new branch is completed in 2022, residents will enjoy a sleeker, more accessible branch library. But as thrilling as it may be to fly into the future, let’s take a note from the Sankofa bird and pause to consider the past.

A Historic Neighborhood

“Historically, Hough has always been a special place in terms of what Cleveland means to the African American experience,” says Ward 7 Cleveland City Councilman Basheer Jones. “Since it was known as Station Hope on the Underground Railroad, Cleveland has played a multicultural effort to bring liberation to fellow human beings—and Hough is historically a neighborhood that has fought for liberation.”

Councilman Jones is referring to the Hough Uprising of 1966, when interracial tensions in the predominantly Black neighborhood boiled over due to discrimination, segregation, inadequate housing, and police brutality, among other factors. The narrative surrounding the uprising—once commonly known as the “Hough riots”—has shifted over the years to accommodate the broader sociopolitical tensions that played a role. This piece of Hough’s history speaks to the ongoing fight against racism and inequality, which Cleveland Public Library centers in its work to create inclusive public spaces.

“The Hough Uprising is part of the history of this neighborhood, but a lot of people don’t know what this neighborhood has been through,” says Moody. “This is an opportunity for the new building to be a resource reflecting that history.”

Sanders adds that Hough was a bustling community in the late 1950s, and perhaps the new Hough library branch—along with the greater E. 66th Street Corridor project heralded by the Cleveland Foundation—may help return some of that energy to the neighborhood.

“This is a neighborhood of resilience, consciousness, and love,” asserts Councilman Jones. “We have trials like everyone, but at the end of the day, we’re here, and we’re not going anywhere.”

A Study of Contrasts

Keith J. Benford may only be 19 years old, but he has a lifetime of history in the Hough neighborhood, which he describes as a study of contrasts.

“The Hough community has every motif you can find in Cleveland. It’s like living in a Picasso painting,” Benford says. “If you walk around, you might see industrial spaces, barren land, a new vineyard, League Park, an apartment complex, then a house almost like a mansion. There’s a juxtaposition between nature and industrialism here, just as there’s a juxtaposition of privilege and non-privilege.”

Benford grew up near the lot where the new Hough Branch will be constructed, a space where he experienced many “serene and sacred moments.” He recalls the fleeting beauty of flowering trees, summers spent exploring wildlife with friends, and the snowy day he ran into that field to pray after receiving a college acceptance.

Because this space played such a pivotal role in his life, and because he respects nature, Benford was initially skeptical when he learned a new library branch would be built there. He shared his concerns with the Library staff, who are now exploring ways to either preserve some of the plant life or incorporate native plants into the landscaping design. Despite any lingering apprehension, Benford recognizes the value of having a brand-new library in his backyard.

“Libraries in Cleveland cater to the communities around them,” he says. “This branch can be a place for kids to hang out, a place to learn—especially Black history, non-Eurocentric history, and African history. There’s a myriad of possibilities.”

Engaging community members like Benford in this reimagining of Hough Branch has been an imperative part of the process.

“The library is not just a brick-and-mortar place. It needs to be active in the community,” Councilman Jones says. “Ward 7 residents have been a part of this from the beginning, and I’m excited there’s been so much community input into how the library will look, what it will contain, and what it can do. This shows our children that we’re invested in their education and their literacy—that they mean something to us.”

Hough Today, Hough Tomorrow

In 2019, Cleveland Public Library celebrated its 150th anniversary, a milestone that prompted many to question what the next 150 years might bring for library services. While a global pandemic may have altered in-person programming for the time being, a brighter future awaits—and that future requires planning and visionary action today.

When we see new buildings in Cleveland, we rarely see a new library, especially in the Hough neighborhood. To see the realization of this is very exciting.

Basheer Jones, Cleveland City Councilman, WARD 7

“We really need libraries. We’re in the midst of the pandemic but also social change and strife, and we need places for people to convene, to share ideas, and to receive services,” Sanders says. “When we design a new branch in a community like Hough, I think of what that community will look like 50 or 100 years. The world will change, but the library will still be there to help people get the nourishment they need for their mind, body, and soul.”

Like the Sankofa bird, which looks back as it prepares to move forward, creating a new library branch calls for both an awareness of the past and the confidence to stride boldly into the future—and the Hough neighborhood will have just that when its new branch library opens in 2022.

Meet Moody Nolan

Jonathan Moody, AIA, NOMA, NCARB, LEED AP

Chief Executive OfficerIn early 2020, Jonathan Moody took over the reins as CEO of Moody Nolan from his father, Curtis J. Moody, in the kind of family succession that is rare in the architecture industry, but particularly for a minority-owned business.

Jakiel Sanders, AIA, NOMA

Project Architect“The new branch will be a dynamic piece of architecture, something forward-thinking and representative of the 21st century—a symbol to show that people care about this community.”